By Rakiya A.Muhammad

The sun reflected off Sokoto’s dusty roads as Hon. Ubaida Muhammad Bello began her campaign, undeterred by the heat and determined to challenge norms. Her address symbolized hope for women whose stories too often fade into the background.

Women fill polling stations with hope in their eyes, casting record votes—yet Sokoto has never tasted a woman’s victory. Hon.Ubaida’s persistent efforts exemplify resilience in a space where women’s political representation is rare.

Still, the harsh reality lingers: women in Sokoto’s politics are shadows, their voices lost in silence. Hon.Ubaida’s political ambitions ha

ve faced repeated obstacles. Her initial attempt occurred in 2011, when she contested for a seat in the Sokoto State House of Assembly under the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), encountering scepticism and cultural barriers.

“It was taboo for a woman to participate,” she recalls. “Supporters were afraid of social repercussions, but I persisted with my husband’s backing.”

Although she did not win that year, her resolve grew. She made a subsequent attempt in 2015 as a candidate for the All-Progressives Congress (APC). However, her campaign was quickly undermined by what she identified as ‘godfatherism,’ referring to influential political actors who excluded her through unofficial means, such as informal nominations.

“Just overnight, I received a call from an important guide in politics. He has been a pillar throughout my political struggle. He said my constituency had told him to ask me to step down for a man,” she laments.

“I come from a local government in the heart of the ancient city. They said they couldn’t vote for a woman or even allow their women to go out. I should please step down for a man—someone who hadn’t struggled or fought for it, regardless of capacity or what I could bring to Sokoto.”

Hon. Ubaida had strongly believed she would become the first female legislator in Sokoto State, so being told to step down cut deeply. She felt crushed. She remembered all she had poured into her campaign: every hard-won relationship with her constituency, every handshake with youth and women, every promise made. She was swept aside with a word, with no vote, replaced by someone who had not weathered the same storms. “Since then, I lost confidence. I said I couldn’t waste my time anymore.”

Her experiences are indicative of a broader, persistent trend of societal resistance grounded in patriarchal systems. Many point to cultural constraints, misinterpretations of religious doctrine, and entrenched gender biases as the roots of this silence. As Malam AII, a local teacher, notes, some wield faith as a shield to keep women from leading. “They don’t want women to be in leadership positions, so sometimes they misrepresent facts to achieve that.”

Electoral Landscape and Women’s Participation

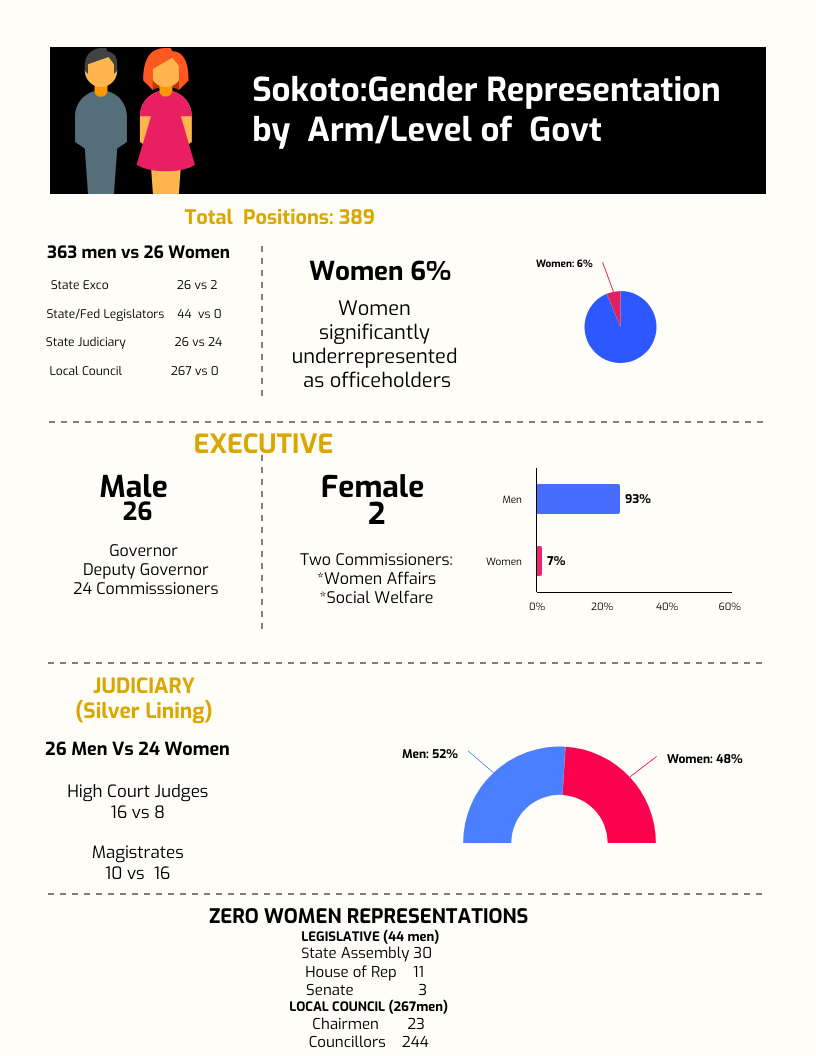

Sokoto is among the few Nigerian states with no female representation in elective offices.

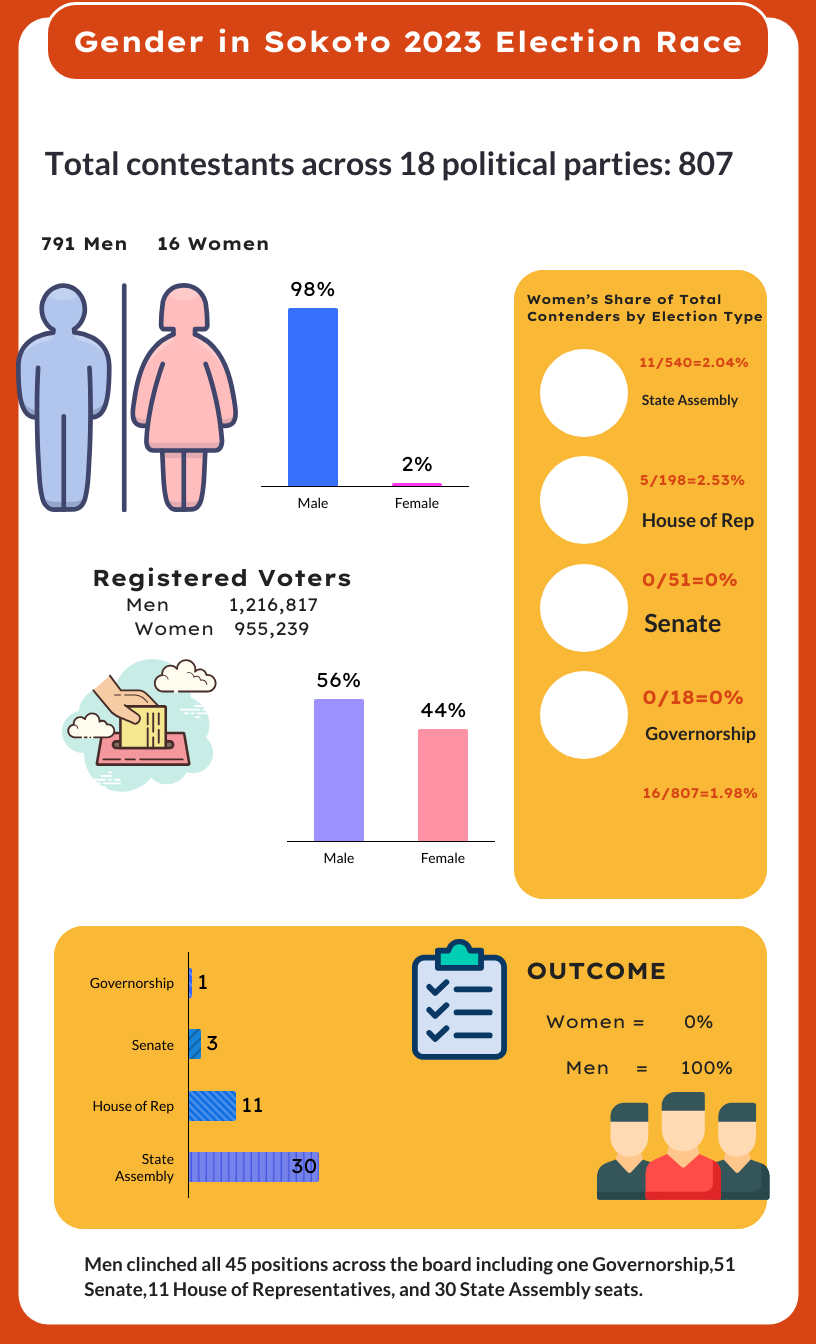

In the 2023 General Elections in Sokoto State, out of a total of 45 positions contested—including one Governorship, 30 State House of Assembly, three Senate, and 11 House of Representatives seats—not a single woman won any position.

According to INEC’s report for the 2023 general elections, there were 807 candidates competing for the 45 available positions: 18 for the Governorship, 540 for the State House of Assembly, 51 for the Senate, and 198 for the House of Representatives.

A report by CDD West Africa noted that 11 female candidates ran for the State House of Assembly and five for the House of Representatives.

Out of 45 candidates vying for elective positions in Sokoto State in 2023, only about 2% were women, and not a single one emerged victorious.

Despite constituting a substantial proportion of registered voters, women exert limited influence in politics. INEC data indicate that, of the 2,172,056 registered voters in Sokoto State for the 2023 polls, 1,216,817 were male and 955,239 were female.

These figures demonstrate a significant disparity. Men account for 56.02% and women for 43.98% of registered voters, resulting in a 12.04% gender gap in registration. This disparity increases substantially at the candidacy level, where men occupy 98% of candidate positions and women only 2%.

Musa Bala Shuaibu, Sokoto State INEC Training Officer, notes that the commission has introduced measures, such as gender desks and targeted stakeholder engagement, to involve more women; however, significant structural barriers still hinder progress.

Political Parties and the Marginalization of Women

Major political parties contribute to the ongoing marginalization of women. While some parties, such as the Action Peoples Party (APP), have supported female candidates in various roles, mainstream parties have not provided opportunities for women to participate.

Abba Sidi, Chairman of Action Peoples Party (APP), who is also Chairman of the Coalition of United People Parties, Sokoto state, notes, “In the 30-seat State Assembly, no woman was given a chance. Our party supports women—our secretary, deputy gubernatorial candidate, and nine aspirants in 2023. But the major parties do not give room for women.”

Hajiya Salamatu Abdullahi Isah, who contested the 2019 gubernatorial election, underscores the systemic exclusion: “Major parties rarely allow women to contest; they often replace women aspirants with men after primaries. It’s a deliberate sidelining, not a matter of capability.”

“I joined the Progressive Peoples Alliance (PPA) because I believed it would let me participate fully. Other parties would never give women the chance. Many women hope to contest, but ultimately must withdraw so male opponents can take the position. I have seen that repeatedly,” she points out.

“That’s why I joined PPA. Alhamdulillah, I achieved my goal. I contested, went through the primaries, and my name was included in the INEC list. I was the party’s contestant. Although I didn’t win, I know I gave it my best effort.”

The former gubernatorial candidate adds: “It is one thing to contest and win or lose, and another not to contest at all. In other parties, you cannot tell me a woman contested. Not a single woman has ever contested, let alone won.”

Hajiya Salamatu began her political career with the registration of the PPA, becoming one of its earliest members and the third person listed on the party’s register in Sokoto.

She first served as the party’s women’s leader, advanced to state chair, and eventually contested for the governorship.

“My political experience showed me how party systems sideline women. If given the chance, I would change that perception because exclusion starts within the party,” she says.

“I was moved to run for Governorship in Sokoto State to give voice to women, convinced our presence went unrecognized. We fill the lines on Election Day with hope, yet we remain unrepresented,” she bemoans.

“After the election, all we got is the Commissioner of Women’s Affairs. Even in the budget, that position is not in the sixth or seventh category. When they claim to be assisting women, it is often limited to providing things, such as tailoring or knitting machines, soap, or detergent. That’s all.”

Hajiya Salamatu felt women were above that.” I decided that if I had the chance, I would prove women can do better.”

She remains sceptical that major political parties will provide opportunities for women to become candidates.

“There was a time we tried that, at least let’s have one woman in the state assembly to represent women, but all the major political parties refused,” she recalls.

Hajiya Salamatu stresses that culture and religion are not to blame. “Sokoto is far behind, and don’t blame religion or tradition. Women in Sokoto are often unaware of their rights and are not eager to learn about them. They believe their job during elections is to work for men, hoping to get the position of Commissioner for Women’s Affairs or Special Adviser without portfolio.”

“Therefore, there is nothing culturally or traditionally at fault. Men and women share similar experiences in school and during campaigns, including late-night activities. It is not religion. The sooner women realize this, the better—and now is the time for women to boldly claim their rights, support one another, and insist on fair representation.”

Legal Frameworks, Cultural Myths

Nigeria’s constitution proclaims citizens’ right to participate regardless of gender. Barrister Rasheedat Mohammed, the first female Chair of the Nigeria Bar Association Sokoto chapter emphasizes: “There’s no legal barrier to women’s political participation. The obstacles are cultural and rooted in the male ego.”

She recounts her experience contesting for the positions of NBA State secretary and chair – roles traditionally held by men.

“At the time I decided to contest for the position of secretary, we had never had any female contest for that position. In fact, there was hardly an election in my branch. They nominated,” Barrister Rasheedat reveals.

“The journey was tough. It was chaotic. There was a male counterpart, and there were people who believed that women should not take certain positions.”

Despite threats and intimidation, she remained confident and ultimately won convincingly.

Also, for the NBA Chairmanship position, she recalls: “Once again, I beat a male counterpart in the election. This time, it was keenly contested because some people swore, they would never allow a woman to lead the NBA of Sokoto branch.”

Women Against Women

Rasheedat, Ubaida, and Salamatu lament the reluctance and lack of support among women for female candidates, which they attribute to various factors, including social norms, internalized biases, competition, and a lack of collective empowerment. They note that the phenomena hinder efforts to improve gender parity in political representation.

“All my support as the secretary and as the chairman of the NBA was from men. 99 percent of women campaigned and voted against me. If I were fair to myself, I would say men are supporting this cause more than women,” the NBA Sokoto Chair discloses.

“A lady joined the political race in Sokoto some years back, and up to the night of the primary, the women were supporting her. But on the day of election ,she didn’t see any of them ,none of them ,they all disappeared ,up till now she said she cannot explain what happened ,is it they were intimidated or they were given money ?she doesn’t know, before then if they were going out they used to go our enmass ,until that day that they were supposed to come for the primaries.”

For her part, Hajiya Salamatu blames women for the prevailing situation of underrepresentation. “It is the fault of women themselves; they are the major enemies of themselves,” she observes.

Hon. Ubaida also shares: “I have that experience of women not supporting women. It’s a serious problem – ‘pulling her down syndrome’; women do not support one another, the envy is there, I believe it’s a lack of capacity, they don’t understand reasons behind the struggle, they don’t understand we can help one another.”

She believes that if there are strong networks and forums where women are sensitized, they will come to understand why ‘pulling her down syndrome’ is bad.

Impact of Zero Representation

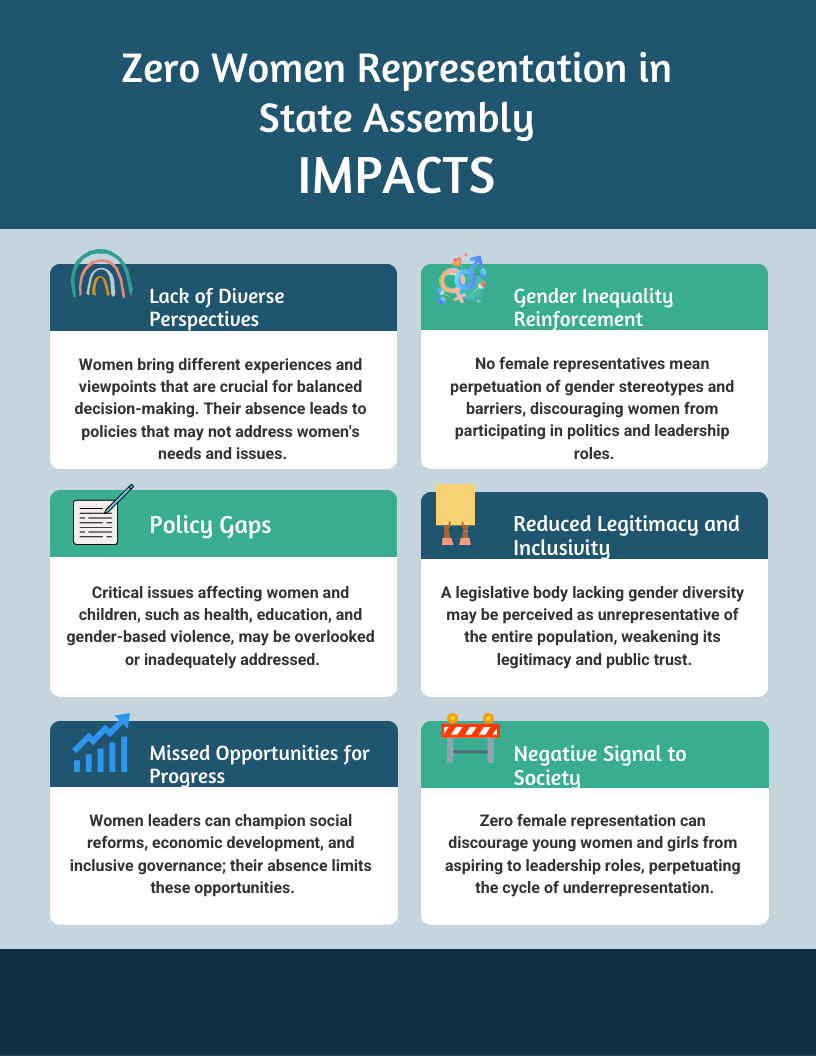

There are currently no women among the 30 Sokoto State House of Assembly members or the 267 local government positions, including the 23 LG Chairs and 244 councillors.

It is unacceptable that Hon. Tukur Umar (Binji Constituency), a man, leads the House committee on Women Affairs. This situation directly undermines gender justice, especially as the country has ratified the United Nations’ Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, a binding commitment to gender equality. Nigeria’s National Gender Policy mandates a 35% affirmative action quota, as reinforced by a 2022 court judgment. Yet, the persistent exclusion of women from the Assembly and other levels of government exposes a clear failure to uphold these legal and policy commitments.

The lack of female representation in elective offices has significant consequences. A cross-section of women notes issues such as inadequate healthcare, insufficient educational infrastructure, and gender-based violence often remain unaddressed due to the absence of female advocacy. They note, for example, that the lack of women in legislative decision-making contributes to the poor implementation of laws related to maternal health, child protection, and gender-based violence.

Amina Usman, a rights advocate, accentuates: “The law is not the problem. The real issue is political will and cultural acceptance. Women’s voices are essential for policies that truly reflect their needs.”

The Case for Reserved Seats

Many argue that reserved seats are vital to breaking the cycle of exclusion. Barrister Rasheedat advocates: “Reserved seats can guarantee women’s participation, especially in a society where societal and political structures are male-dominated.”

“We need these reserved seats because in Sokoto, even in the next 10-20 years to come, we will still not have a woman who will get elected; number one, her fellow women will not support her, number two, very few men will support her,” she posits.

“I just pray that we get these reserved seats. That would be the best way to encourage women to participate because any other way that we are thinking of is always difficult.”

Ubaida adds, “We understand that particularly in the northern part of the country, it’s only laws that would give us the opportunity to represent our constituency.”

“The men do not want us to be there; they have been occupying it for decades, let them continue in their seats, but at least a special seat for women to voice out for women.”

She also observes that a mentorship program is urgently needed, as so many young women brim with promise yet lack the technical skills to thrive. “I see their potential shining through, but without proper support and capacity building, they remain on the sidelines of political life.”

Zainab Bello Aliyu, Chairperson of the International Federation of Female Lawyers, FIDA, Nigeria, Sokoto State branch, describes the Zero representation of women in elective positions as too bad for a democratic setting.

She reaffirms FIDA’s unwavering dedication to championing the rights of women and children through legal action, education, and bold advocacy.

The FIDA Sokoto Chairperson explains that advocating for women’s representation is at the very heart of FIDA’s mission.

In partnership with UN Women, FIDA has organized numerous town hall meetings to rally support for the Reserved Seats for Women Bill, now before the National Assembly. The bill aims to ensure women’s representation in legislative bodies by reserving one Senate seat for women in each of the 36 states and the FCT, as well as additional seats in the House of Representatives and three seats in every State House of Assembly.

She shares that in Sokoto, FIDA held a series of town hall meetings across all three senatorial districts, bringing together a diverse group of stakeholders, including women’s groups, civil society organizations, male allies, religious leaders, and traditional authorities. The Waziri of Sokoto attended and voiced his support for the reservation of seats for women.

They gathered thousands of signatures from people across local governments in support of reserved seats for women, presenting this powerful show of backing at the town hall meetings.

Zainab observes that for a woman to be in an elective position, there has to be a way for them to get there. “For me, I think the reserved seat is one of the major aspects.”

Alhaji Sani Umar Jabbi, District Head of Gagi in Sokoto State and a prominent ‘He-for-She’ advocate, emphasizes the urgent need to increase the number of female politicians in legislative processes that impact women. “If you go to many northern states, you will see men representing women in women’s affairs. You will see a man as the chairman of the House Committee on Women’s Affairs. We don’t want this. We want women to be representing women on women’s affairs.”

However, some, such as Hajiya Salamatu, remain sceptical. “Reserved seats might end up benefiting political elites’ wives and daughters,” she warns, emphasizing the need for genuine societal change alongside legal provisions.

Yet, others have questioned the consequences if women do not secure the reserved seats.

This apprehension is grounded in recent history, specifically in the fate of five gender bills during the 2022 constitutional amendment.

These five bills, rejected by the 9th National Assembly, aimed to address key gender gaps in the 1999 Constitution. Together, they proposed special seats for women in the national assembly, affirmative action for women in party leadership, citizenship rights for foreign-born husbands of Nigerian women, ministerial appointments requiring at least 10% affirmative action for women, and allowing married women to choose their state of origin. Their rejection has only deepened worries about ongoing barriers to gender equality.

Reflecting these unresolved challenges, Barrister Rasheedat notes, “We are advocating for reserved seats, but we should have a contingency plan. What if those in authority refuse to grant us reserved seats? Should we not participate if reserved seats are not provided?”

In line with this, she suggests, “We should begin to explore various strategies to support women to participate.”

Women in Non-Elective Positions

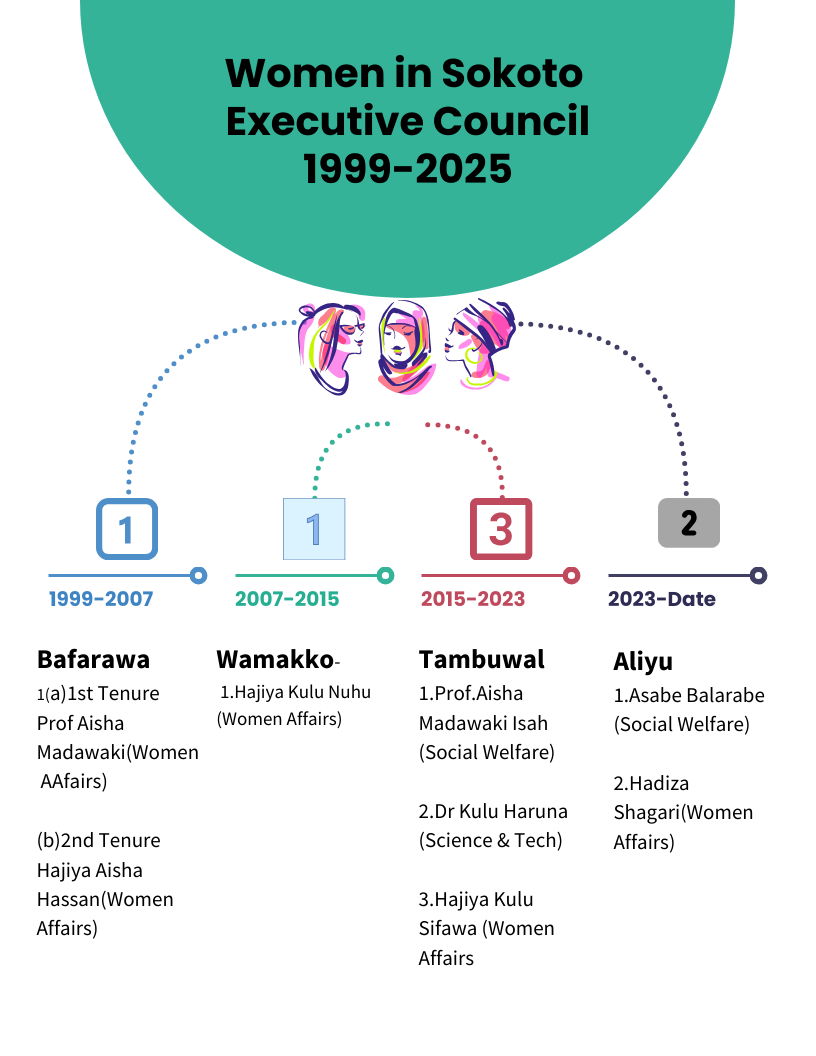

Even in non-elective positions, women are underrepresented. Only two of the 28 members of the State Executive Council are women. The Council includes the Governor, Deputy Governor, and 26 Commissioners.

Since 1999, there has been one woman commissioner under each of the Bafarawa (1999-2007) and the Wamakko (2007-2015) administrations, increasing to three under Tambuwal (2015-2023).

In the current Ahmad Aliyu administration, which began in 2023, two women serve as commissioners. Hajiya Hadiza Shagari leads Women Affairs, while Hajiya Asabe Balarabe moved from Health to Humanitarian and Social Welfare.

In recent years, Sokoto has also appointed more women as Special Advisers.

Under the present government, four women serve as Special Advisers, alongside female directors-general, board secretaries, and directors, indicating a growing presence of women in influential government roles.

Photo-2: Hajiya Hadiza Ahmad Shagari Commissioner for Women and Children Affairs

For the first time, under the Tambuwal administration from 2015 to 202 3, every local government council in Sokoto had three additional seats for a female representative. This bold move led to 71 women serving as councillors during that period, marking a historic milestone for the state.

Though Hon. Ubaida has never been elected, she made her mark as Special Adviser on NGOs, Human Rights, and Donor Agencies during Aminu Waziri Tambuwal’s administration.

“I served as SA. It was the best administration in Sokoto State for women. We had 71 female councillors—never before seen—who represented their wards well. They created many programmes supporting women and children. Those women were respected in their communities,” Ubaida recalls.

“Between 2015 and 2023, three women served as commissioners and six as special advisers. During the 2022 Congress, a 35% quota for women on the executive committee was achieved. These women demonstrated their dedication and excellence, earning respect while working alongside one another.”

Yet analysts point out that while more women are being named to non-elective positions, these appointments can be revoked or changed at any moment by those in power, leaving women without the lasting influence and recognition that comes with elected office.

Additionally, shifting government policies and priorities shape the landscape for women, leading to uneven progress and unpredictable opportunities from one administration to the next.

Silver Lining

Across all branches of government, the Judiciary shines brightest in terms of women’s representation. Women now outnumber men as magistrates, holding 16 of 26 positions, make up a third of High Court judges, and a woman currently serves as Chief Registrar of the Shariah Court in Sokoto.

Achieving an Inclusive Electoral Landscape

The absence of women in the state’s elective offices starkly symbolizes the persistent political barriers they face. Despite their commitment, Ubaida, Salamatu, and other determined aspirants found the state’s glass ceiling unbreakable. Still, these women who challenged the status quo embody resilience, reminding us why the fight for women’s political rights continues.

To achieve gender equality in politics, many advocates comprehensive reforms—promoting gender-sensitive policies, increasing awareness, and empowering women to step into leadership roles.

Reaching true gender parity in representation is not just a matter of fairness but is essential for a truly inclusive democracy that reflects the diversity of its people.

This report was facilitated by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Champion Building component of its Report Women! News and Newsroom Engagement project.