Rakiya A. Muhammad

Shadows flicker across the walls as little Ali shivers in his mother’s arms. His breaths are shallow, his fragile body fights infections it can barely withstand. Ali’s mother’s tears fall onto his fevered skin while she murmurs prayers, clinging to hope that her words will reach the heavens.

In the corner, his father’s grief fills the air, silent but heavy. Every faint heartbeat is a painful reminder of a life slipping away lack of basic nutrition and healthcare

Ali’s story echoes across continents. Frail and small from childhood stunting, he has been robbed of a healthy start. His little body bears the weight of hunger, illness, and neglect. Yet, dreams and the potential for a different life remain within that fragile frame.

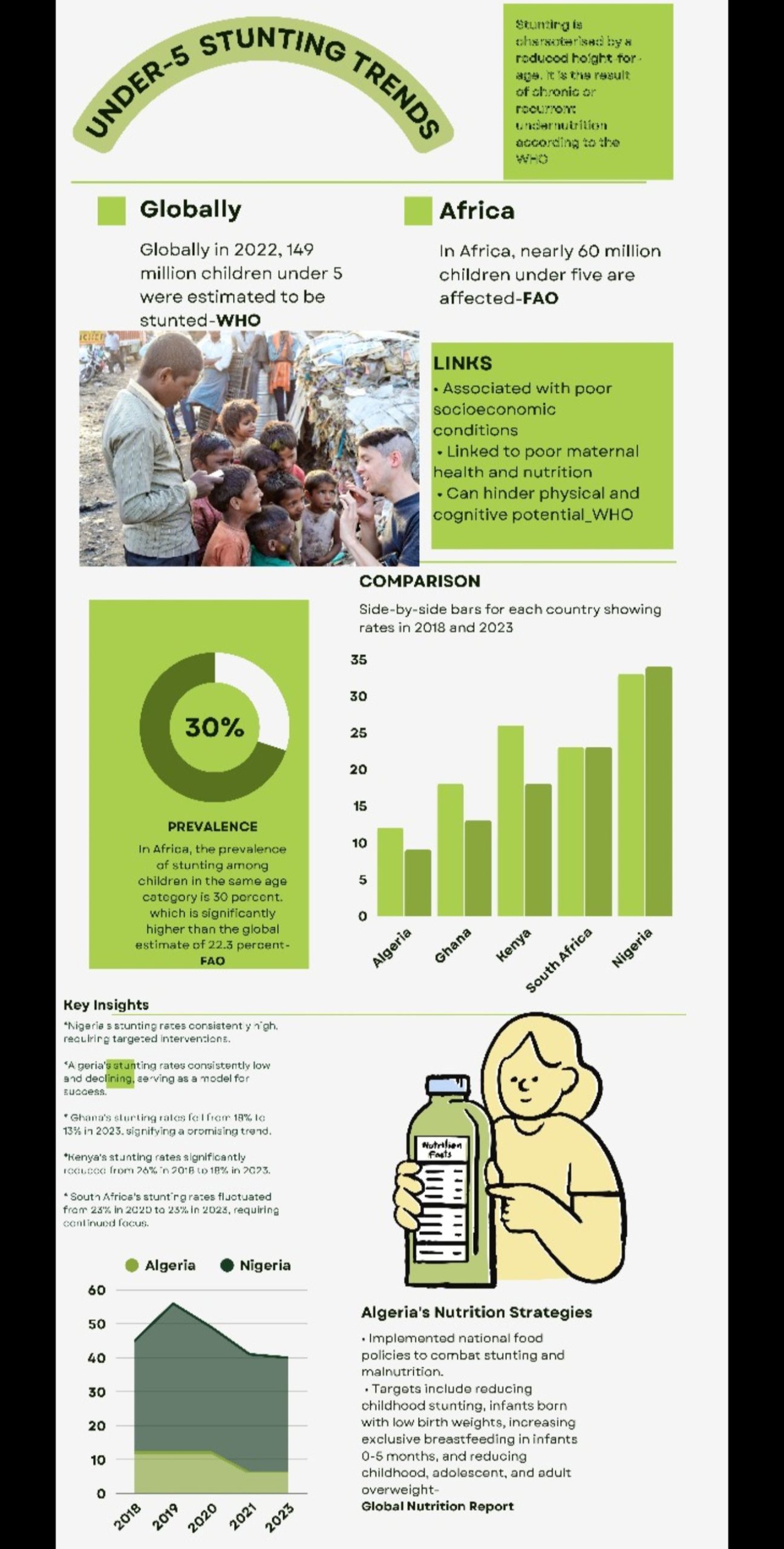

Childhood stunting, described by the World Health Organisation as one of the most significant impediments to human development, prevents children from reaching their physical and cognitive potential.

“Stunting is impaired growth and development that children experience from poor nutrition, relentless infections, and inadequate psychosocial stimulation,” WHO explains.

“It is a result of chronic or recurrent undernutrition, usually associated with poor socioeconomic conditions, poor maternal health and nutrition, frequent illness, and/or inappropriate infant and young child feeding and care in early life.”

Stunting, a form of malnutrition, is a silent epidemic unfolding quietly in communities.

Data links 45 percent of under-five deaths to malnutrition. Each child who dies leaves a grieving family. These deaths, often preventable, result from illnesses made worse by poor growth and weak immunity.

Staggering Numbers, Stark Disparities

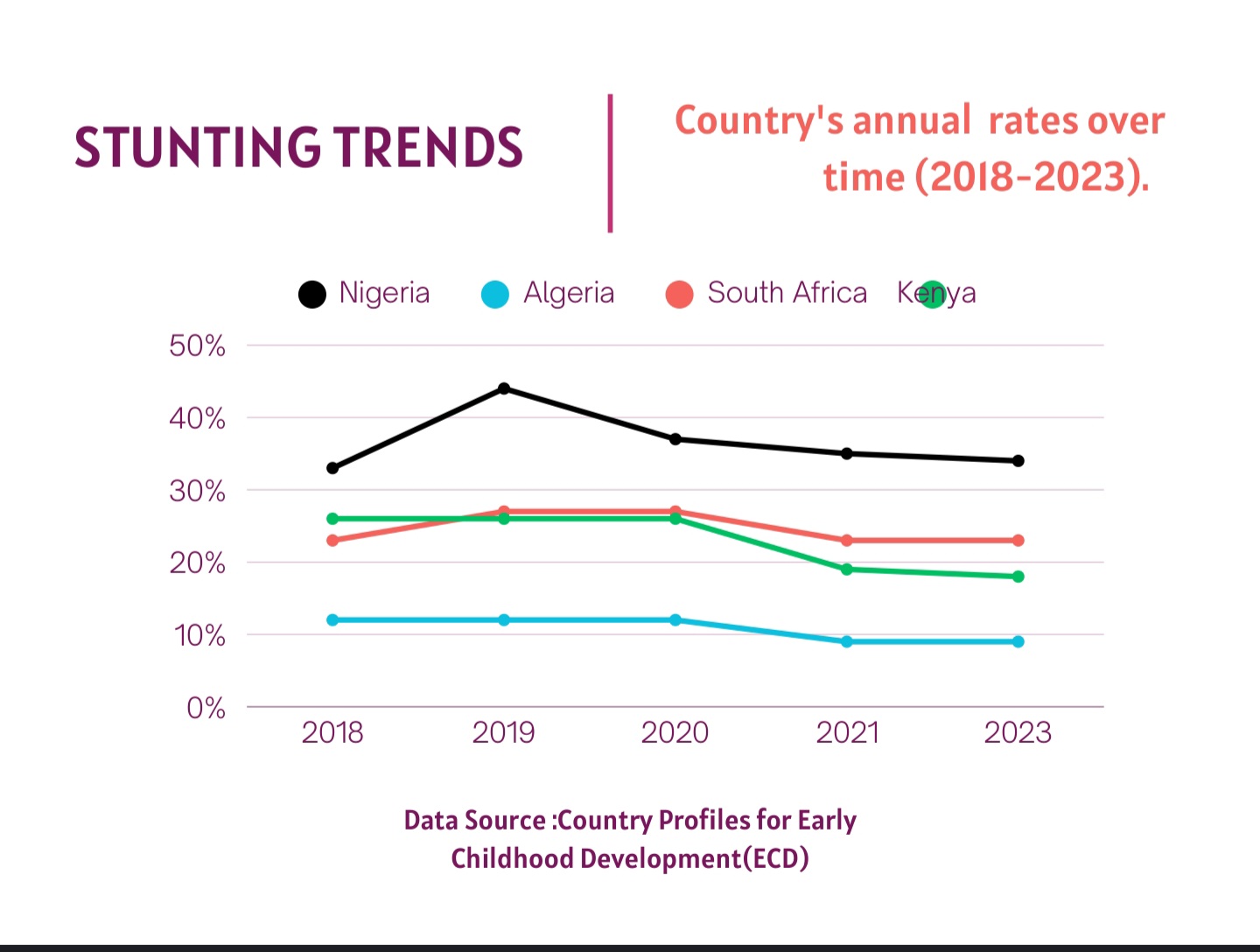

Drawing on the African Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition, the 2022 data reveal a concerning global trend: one in five children under the age of five—approximately 148 million—were stunted. Particularly alarming is Africa’s situation, where 30% of children are affected, forming a stark contrast to the global average of 22.3%.

Behind this figure stands children like Ali. They struggle with delayed growth, fatigue, frequent absences from school, and social exclusion. Each child faces emotional pain and feelings of inadequacy. Their futures are constrained by health and cognitive challenges rooted in early undernutrition.

However, across the African continent, the landscape is diverse. South Africa’s stunting numbers, for example, rose from 23% in 2018 to 27% in 2019 and 2020. They then fell to 23% in 2021 and stayed at that level in 2023.

Conversely, Ghana and Kenya achieved remarkable declines from 24% in 2018 to 15% in 2023 and 26% in 2018 to 18% in 2023, respectively. Algeria has maintained low stunting rates, from around 12% in 2018 to 9% in 2023. proof that targeted efforts can indeed change lives.

Yet in Nigeria, the story shifts sharply. Stunting rates climbed from 33% in 2018 to 44% in 2019. They then slowly decreased to 37% in 2020, 35% in 2021, and 34% in 2023.

Each percentage point represents children like Harira, whose dreams are caged by undernutrition, every day shadowed by empty plates and restless nights. The hope in their eyes dims as poverty, poor maternal health, and inadequate early care quietly steal their futures. Their minds and bodies are held in place, and their childhoods slip away.

Nigeria’s Struggle: A Deep Dive into the Crisis

What caused that alarming spike in 2019? Poverty, conflict, economic instability, political milieu, health crises? Several forces intertwine, forming a complex web of adversity.

Emir Muhammadu Sanusi II, as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Nutrition Society of Nigeria, highlighted a sobering reality during a presentation to the National Economic Council’s first meeting of the year in January 2020.

“Over 12 million children are stunted in Nigeria, while 2.6 million are wasted annually due to malnutrition,” he notes, pointing out that malnutrition accounted for 53% of deaths among children.

Nigeria recorded the highest number of stunted children in Africa, he adds, highlighting poverty, socio-cultural issues, and the political environment as key factors.

The nation’s under-five stunting figures have decreased from 44 percent in 2019, but the rate remains worrisome at more than 30 percent.

“Nigeria has made some progress towards achieving the target for stunting, but 31.5% of children under 5 years of age are still affected, which is higher than the average for the Africa region (30.7%),” reveals the Country’s profile ,Global Nutrition Report.

Mrs. Ladidi Bako-Aiyebusi, Director of the Nutrition Department at the Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, describes the nation’s struggle with a ‘triple burden’ of malnutrition: undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, and overnutrition.

She notes that the crisis’s roots are intertwined with limited access to food, poor feeding practices, and pervasive socioeconomic issues.

Early Malnutrition’s Irreversible Impact

For children like Ayo and her brother, early neglect is a sentence to lasting struggles—sickly bodies, lost chances to learn, and a future forever overshadowed by what could have been.

Ms. Cristian Munduate, UNICEF Representative in Nigeria, underscores a heartbreaking reality. When severe stunting strikes in the first five years of life, it closes doors that can never be reopened.

She explains that severe stunting during the first five years can irreversibly impair cognitive and intellectual growth. Later nutritional interventions cannot undo this damage.

“The problem with this is that these children are not only affected by their weight and height. When you have severe stunting, your brain doesn’t develop well in the first five years of life,” the UNICEF Rep articulates.

“This is irreversible. Even if you later feed the child properly or the stunting stops, once cognitive and intellectual capacities are affected, it becomes challenging to turn back.”

Munduate emphasizes the importance of taking early action to address stunting. “The first 1000 days are important because poor nutrition during this period causes irreversible physical and cognitive problems in the child’s body.”

She notes that the first challenge children face regarding food insecurity is widespread poverty, a situation made worse by rising poverty levels over the past two years.

“A lack of diverse nutrients essential for growth accompanies this food poverty,” Munduate highlights, “So, families do not have the necessary income to feed their children properly.”

Moreover, Munduate adds that multidimensional poverty reveals more profound vulnerability among households. This is especially true for children deprived not only of nutrition but also of health and sanitation. The lack of these necessities affects their capacity and hinders opportunities for life and growth.

Voices from the Ground: Personal Stories, Policy Responses

Fatima, a mother from a rural village, shares her heartbreak: “Sometimes I have to choose between buying food or medicine. It’s devastating to watch my children grow weak because I lack the resources to nourish them properly.”

Similarly, Joshua’s father describes their struggle: “Our son experienced recurrent infections and poor growth since infancy. The doctor told us his immune system was weak, making him more vulnerable to sickness,” he recalls, adding that the family’s limited income was a challenge to meeting the needs.

“We faced emotional and financial stress trying to care for him, often missing work to take him to clinics far from home.”

Their stories do not just reveal the toll of hunger and illness; they also expose the devastating impact of these conditions on individuals. They speak to the heartbreak, the sleepless nights, the anxious waiting, and the silent tears as parents watch their children slip further from health and hope.

Hajiya Aisha Abubakar, a community health advocate, notes that in some communities, families struggling with childhood malnutrition, limited access to healthcare, sanitation, and nutritious foods creates ongoing hardship.

“These children suffer from growth delays and health issues,” she points out. “The lack of resources and infrastructure makes addressing stunting a complex and long-term challenge for entire communities.”

However, on the policy front, there is renewed hope as Nigeria’s lawmakers address the urgent hunger crisis.

This urgency gained prominence at the House of Representatives during the recent inauguration of the House Committee on Nutrition and Food Security.

At the event, Speaker Tajudeen Abbass underlined the committee’s pivotal role in shaping legislative measures to address the hunger crisis, which has been worsened by climate change, inflation, and insecurity.

Abbas cites alarming UN statistics: 26.5 million Nigerians may face severe food insecurity in 2024. Nigeria ranks second globally in malnutrition, with over 30% of children under five suffering from stunting, and 35 million children affected overall, many severely.

He urges the committee to act decisively, using oversight and new legislative frameworks to support agriculture and food supply, addressing crises caused by climate change, insecurity, and outdated practices.

This legislative commitment is presented as vital to combating hunger, sustaining development, and reducing poverty nationwide.

Nigeria’s Coordinating Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Ali Pate, confirms the implementation of a multi-sectoral approach to combat malnutrition, utilizing local, ready-to-use therapeutic foods.

He reveals that the federal government has allocated $11 billion, while UNICEF has contributed an extra $60 million to bolster healthcare infrastructure and nutrition programmes.

Still, the many socioeconomic factors behind this crisis require concerted efforts of all stakeholders to work together to address stunting and malnutrition.

Learning from Success: Algeria’s Model of Progress

While Nigeria faces hurdles, Algeria’s experience offers hope. With only 9.8% of children under five affected—below the African average—Algeria’s comprehensive policies on nutrition, breastfeeding promotion, and maternal health demonstrate that change is possible when determined efforts are made.

The North African country made significant progress towards addressing stunting and other forms of malnutrition through its national food policies. These policies have goals that align with the global nutrition target. The goals include reducing childhood stunting, decreasing the number of infants born with low birth weight, increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates for infants aged 0-5 months, and reducing overweight among children, adolescents, and adults.

Addressing Malnutrition, Not Just About Numbers

Behind every statistic stand children like Ali, Harira, Ayo and Samuel—children whose laughter has been replaced by silence, whose play has been replaced by longing. Their faces, filled with yearning, remind us that this is not just about numbers, but about defending the spark within every child: the right to dream, to grow, and to become all they are meant to be. At the centre of this crisis live dreams and futures hanging in the balance.

With millions affected by malnutrition, addressing food insecurity and improving health outcomes is more important than ever.

“We are all members of the global food system, and we all have a responsibility to act,” remarks Francesco Branca, the Director of Nutrition for Health and Development at the World Health Organisation.

Branca notes that transforming food systems is essential to ending hunger and malnutrition.

The WHO official expresses their commitment to supporting governments and their stakeholders in investigating the intersections between health and food systems and in taking food system actions that positively impact health, both nationally, regionally, and globally.

“By coming together to transform food systems for better health,” stresses the Nutrition for Health and Development Director, “we can contribute to building a world in which no one is hungry, no one is unhealthy from a preventable cause, no one faces poverty, and no one is left behind.”