By Rakiya A.Muhammad

Adetola Rafiu observes the drought-cracked fields surrounding his community, each fissure in the ground a testament to the harsh realities of climate change. His mind drifts back to the lessons his father taught him on the land, an understanding that now faces more challenges than ever. While these challenges include droughts, floods, and shifting seasons, Rafiu and many rural farmers in Nigeria’s Southwest State of Osun remain deeply rooted in their resilience.

Rafiu, a determined crop farmer, explains, “Climate change threatens all that we know, but giving up is not in our nature. We have always watched the land closely and learned from the cues that nature whispers to us. These signs guide us through turbulent times.”

This local perspective serves as a lens for understanding a much broader challenge. Climate change is a pressing global issue—one that particularly threatens agricultural systems and disproportionately affects those who rely on rain-fed farming.

The Institute of Environmental Research and Education (IERE), a leading authority on understanding the connections between agriculture and climate change, notes, “Agriculture is intrinsically linked to climate.”

“Stable weather, predictable rainfall, and moderate temperatures are crucial for crops and livestock. However, climate change disrupts these conditions.”

IERE emphasizes that such disruptions have increased, with more extreme weather, altered rain patterns, and rising temperatures affecting yields and livestock productivity.

The effects of these disruptions reach beyond immediate crop yields. As IERE points out, changing climate patterns threaten not only food security but also the livelihoods of millions relying on agriculture around the world.

Many farmers observe firsthand the impacts of climate change on agriculture. Warmer temperatures and altered rainfall patterns shift farmers’ planting schedules, resulting in unfavourable harvests. Unexpected droughts occur when crops need rain most. Weeks later, floods wash away what little survives.

Prof. Sani Miko, an agriculture expert, notes that such challenges are becoming more predominant. Increasingly frequent floods, droughts, and heatwaves severely damage crops and disrupt agricultural activities. At the same time, warmer temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns favour the spread of diseases.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), describes losses and damages in agrifood systems as a major economic burden.

“Post-disaster assessments from 2007–2022 show that agriculture lost, on average, 23 percent of total disaster impacts,” it says. “Droughts alone caused 65 percent of these agricultural losses. This led to an estimated $3.8 trillion loss in crops and livestock over 30 years.”

Beyond the financial losses, many agricultural families experience greater food insecurity and economic instability, highlighting the urgent need for effective adaptation strategies.

Drawing on Indigenous Knowledge

In tackling shifting weather and uncertain seasons, many local farmers rely on indigenous knowledge, especially because they have limited access to meteorological weather information.

In Osun State, Southwest Nigeria, rural crop farmers adapt to changing climate conditions by drawing on a deep connection to the land, indigenous skills and weather wisdom.

Rafiu shares that farmers combine observations of animal and plant behaviour with atmospheric conditions to predict seasonal climate.

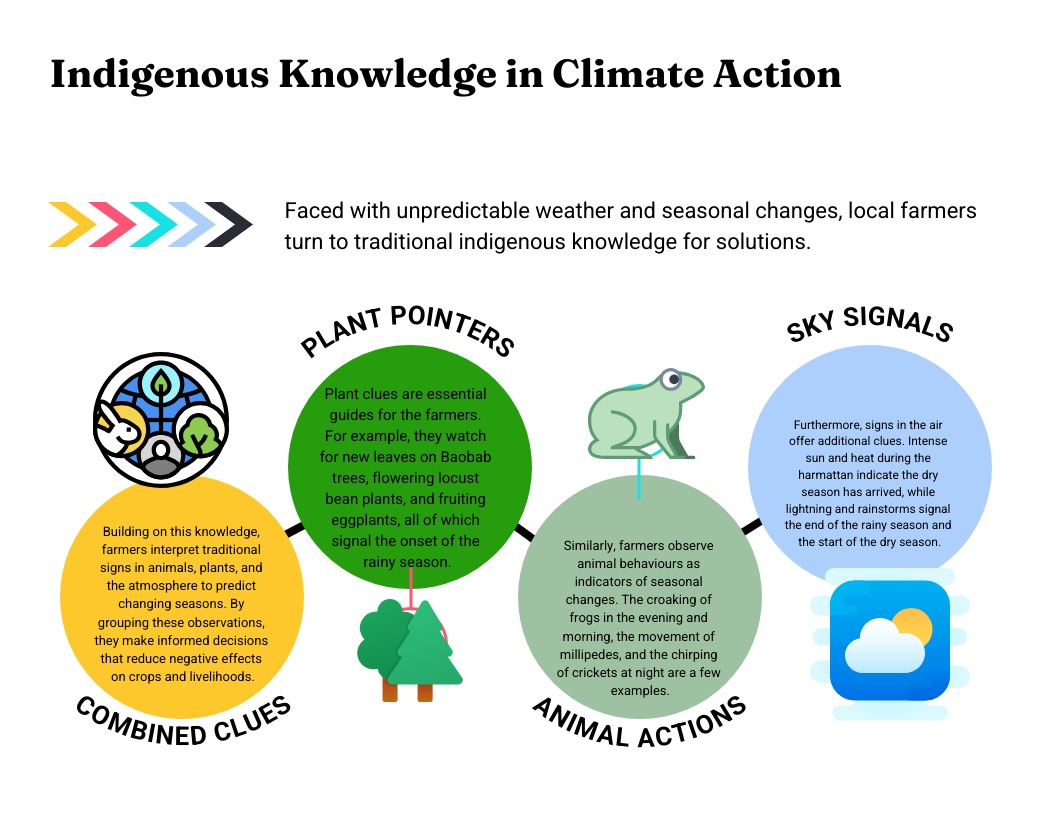

Farmers in the region have developed distinctive indigenous weather-watching systems. Through traditional signs found in animals, plants, and the sky, they predict changing seasons. Grouping these observations helps them make decisions that reduce the negative effects on crops and livelihoods, thus helping to prevent food insecurity.

Animal Signs: The farmers observe various animal behaviours as indicators of seasonal changes. The relentless croaking of frogs in the evening and morning, the movement of groups of millipedes, and the chirping of crickets at night are just a few examples. “The appearance of cattle egrets, an army of ants, and chirping crickets signals the onset of rain for us,” another rural crop farmer Sunday Ishola explains.

Plant Signs: Plant clues also guide the farmers. “We watch for new leaves on Baobab trees,” he says. Flowering locust bean plants and fruiting eggplants also signal the onset of the rainy season.

Sky Signs: Ishola also notes signs in the air. Intense sun and heat during the harmattan indicate that the dry season has arrived. Lightning and rainstorms signal the rainy season’s end and the dry season’s start.

They note the absence of earthworms, the arrival of hawks, and the appearance of dragonflies near water all signal the beginning of the dry season.

“We rely on indigenous adaptation strategies that use natural indicators to forecast weather patterns, an approach that enables us to adjust planting schedules and mitigate crop failure, “says an old farmer, Baba Bola

“The strategy is crucial for managing climate risks in rural farming and has proven effective and reliable over time.”

He says they also cultivate different varieties of crops, rather than relying on a single one, which reduces their vulnerability to climate-related risks. They employ mixed farming, which combines livestock rearing and crop farming, offering a range of options to enhance their resilience in the face of adverse climate change impacts, such as drought.

The farmers also plant trees and shrubs with crops. This shade protects young plants from hot sunlight during the dry season. They harvest rainwater and also use manual watering methods.

For some, including farmers like Ayo Tope, faith also provides comfort and a means of coping with the challenges brought by climate change.

“We pray for rain and good weather. We believe that only He can bring us favourable weather.”

The farmers say their adaptation measures have proven effective in minimizing vulnerability to climate-related shocks.

Beyond Heritage Preservation

However, rural farmers lament the lack of adequate resources and support, which limits the use of indigenous adaptation strategies.

This knowledge, passed down orally through generations, now faces new risks as elders age. Communities fear losing this wisdom, underscoring the need for documentation.

As these traditional methods are increasingly at risk of being lost, many advocate for their preservation and integration, noting that the combined strength of tradition, innovation points the way to a sustainable and secure future for all.

Accordingly, the Institute of Ecolonomics (IOE) and others stress the importance of merging indigenous insights with modern weather forecasts.

IOE is a leading voice for fostering a symbiotic relationship between a strong economy and a healthy ecology, promoting a sustainable future.

“Indigenous communities have spent generations perfecting farming methods uniquely adapted to their local environments. Practices such as crop rotation, intercropping, agroforestry, and organic composting aren’t new—they’ve been used successfully by indigenous people for centuries, “it points out.

“These methods preserve soil fertility, control pests naturally, and support steady yields, aligning perfectly with modern sustainable agriculture principles.”

IOE however observes that despite their effectiveness, indigenous farming practices are often overlooked in mainstream agricultural policy and education. It recommends partnering with indigenous communities as equals to strengthen food system resilience and sustainability.

“It’s crucial to acknowledge, document, and integrate these practices into modern research and development programs, “it stresses.

“Embracing this knowledge helps preserve cultural heritage, promotes social justice, and creates environmentally sustainable agricultural systems capable of feeding future generations.”