By: Rakiya Muhammad

Beneath the sprawling branches of an ancient tree in his abode in the Wurno area of Sokoto, Mallam Aliyu Hassan drifts into memories of a time when donkeys were cherished and honoured.

“My father and grandfather relied on donkeys just as I do now. They weren’t just animals; they were part of our family, part of our survival.”

He recalled the day they acquired their first donkey, how it carried their harvest, fetched water, and kept their farm thriving. These gentle creatures once roamed freely, their brays echoing through the village, weaving a rhythm into the fabric of daily life.

Disappearing Donkeys

“But everything has changed,” lamented Mr Aliyu, his voice thick with nostalgia. “Now I hear stories of donkeys vanishing overnight, taken by traders. Each day, there are fewer. It pains me to see something so dear slipping away from our lives.”

Aisha Usman, a 60-year-old resident of Wurno, also reminisced about the days when donkeys hauled water from wells or carried stones and sand in town. She remembered how they were once decorated and paraded during traditional festivities, especially during Sallah and turbaning ceremonies. “These days, it’s rare to see donkeys in those events,” she said.

A Rapid Decline: The Numbers and Causes

Over the last decade, Sokoto’s donkey population has fallen sharply, threatening both livelihoods and cultural practices.

According to the Director of Livestock Services in Sokoto state, Abubakar Muhammad Maidawa, the numbers have dropped from more than 250,000 donkeys to about 45,000 today. “It’s a significant decline,” he said.

Despite the Nigerian government’s ban on the trade in donkey parts under its export prohibition policy, the illicit market continues to grow. The ban was meant to reduce demand for donkey hides, which are valued for their use in traditional medicine, but it has done little to stop the illegal flow into international markets.

Donkey hides, meat, and internal organs remain in high demand. Traders sell them to middlemen who then move them to countries like China, where they are used in the production of traditional medicinal products. This ongoing trade is driving the decline of Nigeria’s donkey population and raising serious animal welfare concerns, with many animals being subjected to inhumane treatment and slaughter.

The recent arrests and interception of large consignments of donkey parts across Nigeria in the past few months also indicate that the illegal trade is still very much in existence.

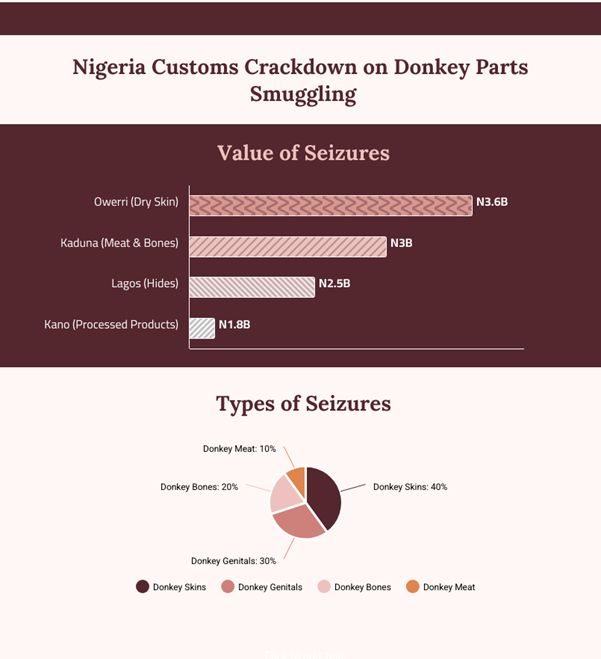

In the last four months, there have been several major arrests across the country. On October 15, 2025, the Adamawa/Taraba Area Command of the Nigerian Customs Service announced that its operatives intercepted 64 complete donkey skins, valued at N112.59 million, being smuggled to China through the Republic of Cameroon. In July 2025, the Nigeria Customs Service intercepted a container-load of 10,603 male donkey genitals along the Kaduna-Abuja Expressway. In June, the Nigerian Customs Service, Federal Operations Unit, FOU Zone C, Owerri, intercepted 13.6kg of dry donkey skin worth N3.6 billion in Owerri, Imo State.

Also, between April 17 and May 17, 2024, the Nigerian Customs Service, Federal Operations Unit (FOU), Kaduna, comprising units in Kaduna, Sokoto, Kano, Jigawa, Katsina, Zamfara, and Kebbi. Niger, Kogi. Kwara and the Federal Capital Territory intercepted two consignments of donkey meat and bones, valued at N3 billion. One of the consignments was a truck with 750 sacks of donkey bones intercepted along Sokoto-Gusau road, while the other included two Canter trucks carrying dried donkey meat along Kontagora -Tegina Road in Niger State.

Fading Footprints: The Multifaceted Pressures Threatening Species

The Zonal Veterinary Officer for Sokoto Central District, Dr Bello Lawal Yahya, noted that a variety of factors are at play. Human activities and ecological changes intertwine to diminish donkey numbers. Market pressure, including illegal trade and the exploitation of donkeys for hides and meat, takes a toll. Husbandry issues, such as inadequate nutrition and poor breeding practices, hinder the regeneration of the donkey population.

Urbanisation reduces traditional donkey habitats, pushing them out of cultural practices and accelerating their decline.

“Biodiversity is dwindling as urbanisation spreads, making donkeys increasingly rare and leaving cultural practices that once relied on them to fade,” he observed.

“Festivities where donkeys were decorated are now scarcely observed, symbolising a broader decline as civilisation reduces their traditional importance.”

Expounding on diet, the vet doctor stressed how nutrition influences breeding. “Many local donkey owners in the state do not provide their donkeys with adequate care. This lack results in delayed reproductive cycles. Time stretches between foals, largely due to poor nutrition.”

Dr Yahya highlighted that nutritional imbalances cause donkeys to grow slowly and develop health problems. He explicitly stated that inadequate nutrition leads to wasting and common digestive issues like colic, which can eventually result in death.

Dr Yahya also noted that donkeys are exposed to stress and discomfort. He explained, “Donkeys often travel very long distances before accessing water, and at times, may go one or two days without any food provided by their owners. So that also causes a lot of discomfort to them.”

Dr Yahya explained that donkeys should have the freedom to exhibit their natural behaviour; unfortunately, they do not, and should be free from stress, but are instead exposed to a range of different stresses. That alone could cause many problems for the donkey population.”

Reliance on imported donkeys, challenges to Indigenous breeds

Support for local breeds is minimal. Many donkeys are imported rather than bred locally. This raises concerns about the potential loss of indigenous genetic lines. Concerns about genetic diversity and local breed conservation arise from reliance on imported donkeys from Niger, Mali, and other countries. When communities over-depend on external sources, indigenous breed development is stifled, and they become vulnerable to market fluctuations and border restrictions.

Trade at the Illela International Market in Illela local government area of Sokoto State, neighbouring Niger Republic, shows this shift. Traders now source donkeys from neighbouring countries. In these countries, breeding is active and supported by both governments and communities.

“We get donkeys mostly from the Niger Republic, Algeria, Mali, Burkina Faso, Libya, and other countries. There is minimal stock in Sokoto, Kebbi, and Zamfara states,” disclosed Abubakar Hassan Zoromawa, Chairman of the Donkey and Horse traders’ union in Illela International Market. The market supplies nearby local markets, including Achida, Bodinga, Gudu, and Goronyo.

Mr Zoronmawa, with three decades of experience, noted that people in the Niger Republic still rely on donkeys for transportation. Many Nigerians, however, have switched to motorcycles and vehicles.

He observed that in the Niger Republic and Mali, many, including women, actively breed donkeys. Influential people and governments there invest in the trade. In Nigeria, however, such support is rare.

The Ripple Effects: Cultural, Ecological, and Economic

The decline threatens more than just the animals. “Relying too much on imported donkeys has consequences. It stifles local breeding and harms communities’ lasting livelihoods,” said Conservation Advocate Abubakar Siddiq.

“Unchecked trade and shrinking habitats could cause trouble. Native species and local ecosystem balance are at risk.”

He also warned that imported animals may carry diseases. “These can affect local populations. Protecting local biodiversity needs careful management of imports and support for local breeds. This helps maintain balance and cultural heritage.”

Heritage Revival: Rejuvenating Indigenous Breeds

Efforts to conserve and improve indigenous breeds include government initiatives, such as artificial insemination and cross-breeding programs. Additionally, the state government plans to protect the local donkey breed while supporting donkey-based businesses, including milk production, tourism, and transportation. By empowering local communities, it aimed to develop pastures for donkeys, ensure a steady supply of feed, and make veterinary care more accessible and affordable.

However, Dr Yahya urged greater research, increased community education, and strong enforcement of animal protection policies as necessary steps to prevent donkey extinction.

He underscored the urgent need for strict enforcement of animal protection laws to halt the decline of donkeys. He warned that waiting puts vital species at risk, as with vultures, which nearly vanished before people recognised their ecological role.

“If we do not act now to improve our protection and care for donkeys, we will only realise our mistake when they are gone,” Dr Yahya cautioned. “We must take decisive steps today and avoid repeating the regret we feel with vultures. Let’s not wait until it is too late, act now to protect donkeys for future generations.”

This story was produced as part of Dataphyte Foundation’s Biodiversity Media Initiative project, with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.